This story is a co-publication with The Examination, a new nonprofit newsroom specializing in global public health reporting. Sign up to get the Examination’s investigations in your inbox. This story is also available in French.

At noon, dusk, and in the dead of night, Cyrille Traoré Ndembi grabs his phone and films his nearest neighbor.

The battery recycling factory roars, rattling Ndembi’s bed. Its chimneys belch smoke into the air, sending bitter odors through the windows of the family’s concrete home. Ndembi’s front garden, where his children play, is sprinkled with a black dust laced with lead — one of the most dangerous metals on the planet.

Ndembi calls one chimney “the tower of death.”

Since moving to Vindoulou, a sandy grid of shacks and homes off the main highway in the Republic of Congo, four years ago, Ndembi’s wife and daughters have suffered from pneumonia, bronchitis, and persistent coughs, medical records show.

“With lead, they say it’s a strong, slow poison,” said Ndembi, 59, who is fighting alongside his neighbors to have the factory moved or closed. “It kills little by little.”

The owner, Metssa Trading, came to Africa from India more than two decades ago under the name Metafrique, seizing upon cheap material, labor and some of the weakest social and environmental protections in the world.

The company is now one of Central Africa’s most prominent recyclers of used automotive batteries; boxes of plastic, chemicals, and metal that — when chopped to pieces and melted inside 2,000-degree Fahrenheit ovens — produce the lead essential to most cars on the road today.

Experts call battery recycling the most polluting industry in the world. At its worst, industry emissions — smoke, dust, chemicals, water runoff — contaminate the environment for generations and the body for a lifetime. The market in Africa is expected to grow to more than $6 billion within this decade.

Yet while India introduced its first lead battery rules requiring recycling companies to adopt safe practices in its own country more than 20 years ago, the Republic of Congo, like other countries in Africa, hasn’t done the same.

Now, officials in New Delhi are celebrating the charge of Indian operations into Africa, which include battery recycling facilities in at least eight countries. India recently dispatched one of its ambassadors in West Africa to inaugurate a plant that had been stockpiling lead batteries. Indian investments in Africa have grown by more than $20 billion in four years, officials say, and government funding for projects across the continent are on the rise. “The sky is the limit,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in August.

This support comes amid growing evidence that Indian lead recycling companies are among the top polluters on the continent and are poisoning nearby communities, an investigation by The Examination, The Museba Project in Cameroon, and Ghana Business News in Ghana has found.

One major Indian recycler was determined by scientists to have contaminated soil not far from schools and churches in West Africa by thousands of times the level that would require cleanup in the United States. Another company, named for an elephant-headed Hindu god, was briefly closed by authorities in Senegal after health violations. Residents in one Kenyan community have tried for years in local court to sue an Indian-owned company, alleging the factory caused sickness and death.

Metssa Trading, too, has come under fire. The Republic of Congo’s environment minister suspended operations here after the factory failed to submit an audit. In neighboring Cameroon, where the owner of Metssa Trading founded another battery recycling company, environment officials rated the plant zero out of 100 in terms of efforts to protect human health.

“Indian companies came to take advantage of our loose monitoring regime,” said John Pwamang, the former acting executive director of the Environmental Protection Agency of Ghana, where 3 of the 6 major battery recycling plants are Indian-operated. “They should invest in modern, cleaner technologies instead of trying to get lead cheaply and contaminating the environment.”

From Ghana to Cameroon, interviews and documents show, government officials repeatedly sided with companies and not the communities that complained of sickness. Officials have refused to share with the public everything from basic information about the results of inspections and cleanups to answers about why they allowed new homes to be built within meters of a factory, despite laws designed to protect human health. Authorities have witnessed unsafe practices, but declined to intervene, the news organizations found.

Corporations from Spain, Ireland, and the United States fuel the toxic ecosystem, buying tons of the dangerously produced goods, which dock in ports from Antwerp to Baltimore, records show.

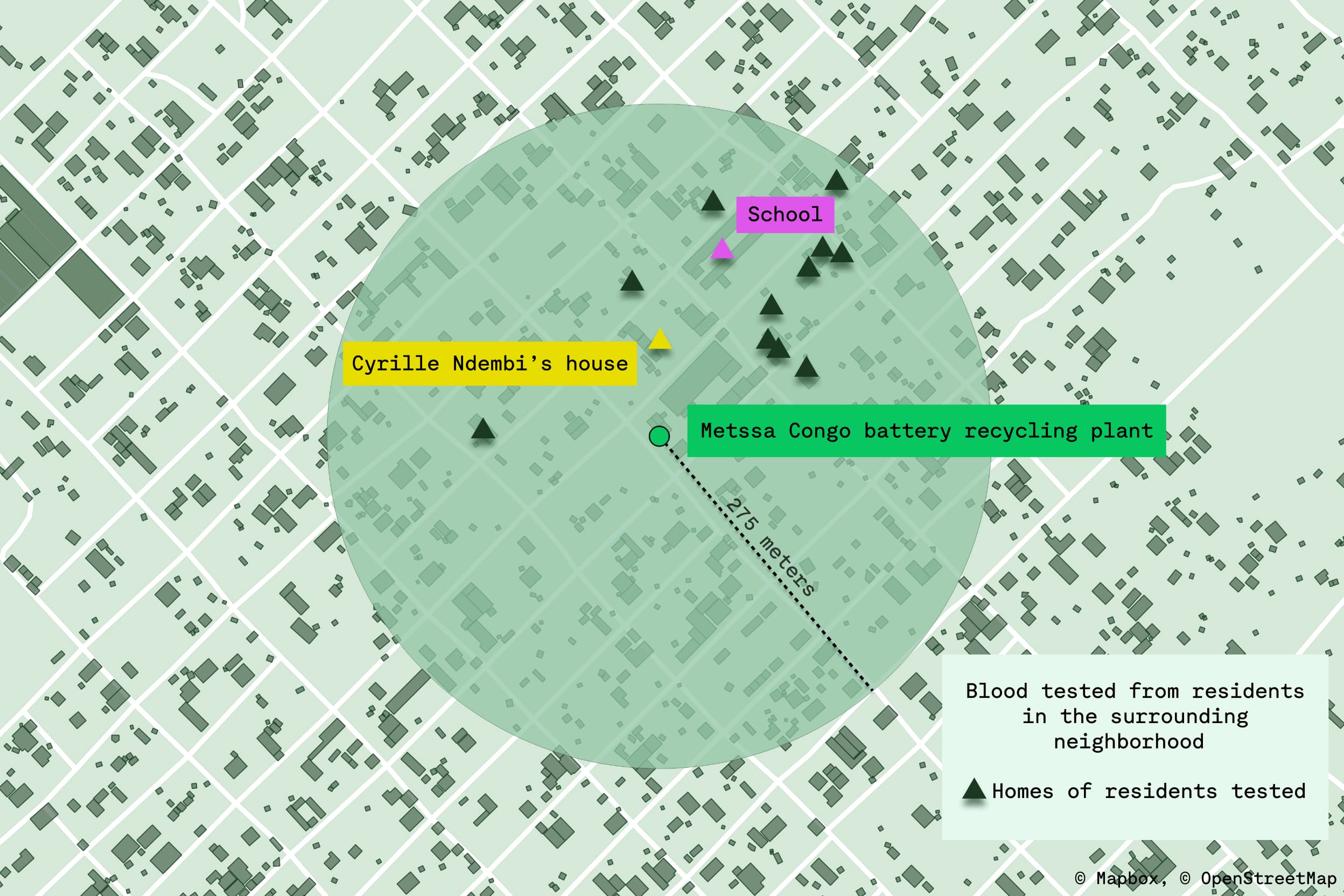

To gauge the risk of Metssa’s operations, The Examination commissioned independent testing in the Republic of Congo and Cameroon.

Nurses conduct blood testing for lead for community members in Vindoulou, Republic of Congo, in July 2023. Will Fitzgibbon / The Examination

Lead levels in all blood samples taken from people living near the Vindoulou factory exceeded five micrograms per deciliter, the World Health Organization’s threshold for “action to reduce or end” the exposure.

Children fared the worst, with results many times higher than the WHO threshold. Doctors called the results “terrible” and “dangerous.”

In Cameroon, scientists gathered soil samples inside and outside a battery recycling plant in Douala. There, more than half of the results identified lead levels that experts agree pose a threat to human health.

“These are very worrying results,” said Gilbert Kuepouo, a geochemist who took the soil samples.

Days after The Examination questioned an environmental regulator in Cameroon about the plant’s activities, he inspected the factory and found problems with the emissions-filtering system. The company agreed to suspend operations and take steps to curb pollution, the regulator said.

The Examination based its reporting on the analysis of test results, lawsuits, videos, medical records, government inspections and correspondence, interviews, and visits to factories and nearby neighborhoods. The investigation drew on records from nine countries to document the expansion into Africa of battery recycling plants from India — the world’s largest democracy and one of its most influential economies.

Metssa’s owner, Arun Goswami, told The Examination the company operates in accordance with all government requirements. “In this global economy, people find opportunities and try to work hard to make their dreams come true wherever they can,” Goswami said.

Earlier this year, Ndembi darted through his neighborhood, accompanying a team of nurses carrying tourniquets and syringes. “Knock, knock!” Ndembi shouted, leading the nurses into the homes of his neighbors to gather what he considered evidence for the battle ahead.

“Our fight is to not leave an unhealthy environment for our offspring,” Ndembi said.

He watched as a nurse struggled to find veins in the tiny arms of his youngest daughter, Cyrfanie, a 15-month old whose favorite cartoon follows a mischievous French Donkey. The nurse instead pricked the sole of the little girl’s foot with a needle, drawing blood into a tube that was then sent to a laboratory overseas.

Ndembi was expecting bad news. The results were worse than he imagined.

Cheap, but deadly

Represented on the periodic table by the symbol Pb, lead has been making people sick for centuries.

Ancient Romans, who sweetened wine by boiling grapes in lead vessels, noticed regular drinkers became sluggish. Children and diners in 19th-century England became ill after eating candies and cheese laced with colorful lead pigment.

From the start of the 20th century, doctors and medical researchers reported that lead in paint and gasoline was linked to psychological conditions that in extreme cases required the use of straitjackets — and led to other illnesses and death.

Lead most often enters the body when someone breathes polluted air or swallows a tainted liquid or solid, like food, paint chips, soil, or dust.

Once in the system, lead moves through the bloodstream, settling in organs and teeth and breaking down cells that protect the entire body.

No amount of lead is safe for humans, although its effects can differ greatly. With the same level of lead in their blood, one person may complain of stomachaches, another may experience brain swelling, and a third may display no symptoms at all.

Exposure can cause brain and nerve damage and has been linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. At extremely high levels, lead can result in seizures and death. Children are especially vulnerable: One recent study calculated that, globally, lead may have cost young children hundreds of millions of IQ points in 2019 alone.

Africa, by one measure, misses out on billions of dollars more than any other region each year in lost productivity caused by exposure to lead.

Recycling lead, a process present on every continent except Antarctica, has long been recognized as a serious public health threat.

“There are very few industries that are this hazardous to health or have this many costs to the general public,” said Perry Gottesfeld, executive director of San Francisco-based Occupational Knowledge International, who has studied battery recycling plants in more than a dozen countries.

Most recycled lead is used in batteries that power automobiles, motorbikes, cranes, and other pieces of equipment central to daily life, including millions of new cars that hit roads every year. Each car will, on average, use four lead batteries over its lifetime. Even most electric vehicles that run on newer lithium batteries still also contain traditional lead acid batteries.

Up to 99 percent of a traditional car battery can be reused, making it one of the most recycled products on the planet.

The lead can be “infinitely recycled,” according to the United Nations body that advises countries on hazardous waste. Recycling can also be cheaper than mining lead ore from the ground. Used battery acid can be dried into crystals to make glass and detergent. Plastic shells, ground into pellets, become planters, trash cans, or new battery casings.

But not all battery recycling operations are alike. There are more than 29,000 backyard recycling sites worldwide, including open-air scrap yards where adults and children work without government authorization or protective equipment, disassembling batteries by hand, thwacking them with machetes and draining acid onto the ground.

Gottesfeld said pollution-control technology makes all the difference and that plants in the United States, China, and elsewhere have improved in recent decades.

“We know this is feasible and doable,” Gottesfeld said of proper protocols. “It can be expensive, but it’s not rocket science.”

Blood tests and toxic dust

To map India’s battery footprint in Africa is to travel from the coastal swamps of Mozambique to mango farms in Nigeria, from small plants in the countryside to entire blocks in the heart of teeming cities.

In the Republic of Congo, Ndembi’s home is a 10-minute walk from National Highway Number 1, down paths of sand that cakes your shoes and toes.

One of Ndembi’s closest neighbors is a former soccer star, a father of four known as “The Knight.” Others are teachers, a veteran, and a retired journalist. Nearby, women sell dried fish outside tin-roofed homes. Blue paint shrivels on the walls of a hair salon named “The Beauty of Man.”

Metssa Congo (formerly Metafrique) moved into Vindoulou more than a decade ago at a time when the neighborhood was sparsely populated. As the years went by, more and more people built homes in the area. A school opened.

Ndembi first visited the neighborhood in 2019. He remembers seeing the factory, but said it stood silent and nobody mentioned any reason for worry. The company had held no public meetings about its activities.

The area was classified as “urban” at the time, official documents show.

Ndembi assumed things were safe.

It wasn’t long after he started building his two-story dream house that signs of trouble emerged.

First came an inspection by health officials who identified unsanitary working conditions in the plant and the risk of soil and air pollution. Months later, Metssa Congo paid $500 to the owner of a local bar who blamed the company for his daughter’s lung infection and who complained that emissions had corroded his roof. The bar owner took the money after promising to “never return to knock on the door” of the company or government officials, according to the agreement.

In 2020, the Republic of Congo’s environment minister halted activity at the plant, then quickly lifted the suspension on the condition the company comply with environmental standards. Soon after, three judges listened in a courtroom downtown as a father of 14 sued Metssa, alleging pollution had sickened him and his children. The man submitted a medical report confirming that his bronchitis was most likely caused by the inhalation of toxic smoke, court records show.

Last year, a team of consultants hired by the company to audit the plant found unhealthy levels of air pollution and warned “toxic dust” could cause cancer, damage to the nervous system, and lead poisoning.

Metssa Congo had no plans to manage risk, waste, or chemical products, according to the audit, obtained by The Examination. The recycling company also did not produce an impact assessment before starting work, the audit found. Such assessments have been required by law in the Republic of Congo since 2009.

“This is negligence on the part of the administration,” said Brice Sévérin Pongui, a Congolese attorney and environmental law specialist.

Pongui said the government sometimes compromises environmental and public safety for economic reasons, including the need for rapid job creation.

The audit acknowledged that the plant financially benefited the town and that its taxes helped the entire country.

Arsène Bisnault, whose consulting firm prepared a separate environmental review, told The Examination the factory should be relocated given the danger of its products.

Bisnault said he stopped work after Metssa Congo did not provide all the documents he requested to perform environmental safety checks. The company still owes him money, Bisnault said.

Earlier this year, Ndembi took the long journey into town to retrieve results of the blood tests. He had spent enough time learning about lead to suspect something was wrong, Ndembi said, but was surprised by his daughters’ results, especially that of the baby, Cyrfanie. Her lead level was the highest in the family.

“I was very upset, very angry,” Ndembi said. “No one in my household was spared.”

Cyrfanie’s test showed more than 53 micrograms of lead — nine times higher than the World Health Organization’s recommendations for intervention.

At that level, according to widely cited standards published by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a child should undergo an X-ray, a neurological exam, and consider admission to a hospital. For anything above 45 micrograms per deciliter, the New York State Department of Health says, “Your child needs medical treatment right away.”

Experts say Cyrfanie is likely to experience significant lifelong impacts. Learning disabilities and brain damage are among the risks at her level of exposure.

One of Ndembi’s other daughters, 8-year-old Cyrielle, also had a result above 45 micrograms per deciliter. Ndembi’s own result was close behind.

The body’s normal blood lead level is zero micrograms per deciliter, said Dr. Brian Schwartz, a professor at John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. “That is none, nada, zilch, zero.”

Ndembi said he doesn’t have money for medical care. The treatment often recommended for severe lead poisoning, known as chelation, can be expensive and the clinic that collected the blood samples said it knew of no available treatment in the Republic of Congo. In any case, the World Health Organization advises that chelation is of limited value when children continue to be exposed to lead.

To better understand risks to the lead recycling plant’s neighbors, The Examination commissioned 10 additional blood tests from people who live near the plant and had them analyzed by a laboratory in France.

Of the four children tested, all had extremely elevated lead levels. The level in one 13-year-old boy, who lives behind the plant, had increased since his first test four months earlier to more than 40 micrograms per deciliter. Another boy, 10 years old, had a result of nearly 46.

Schwartz called the results “outrageous.”

“The key is to eliminate any further exposure,” he said.

In a statement, Goswami, 56, denied Metssa Congo had contributed to elevated lead levels, saying testing done by the local health department “indicated no long-term health effects associated with our operations.” Goswami declined to provide details or documentation about the tests.

The Republic of Congo’s Ministry of Health did not respond to messages, phone calls, and a hand-delivered letter requesting further information.

Goswami said Metssa Congo operates “in strict compliance with internationally recognized industry standards and the approval of the Congolese government,” adding the company increased the height of its chimneys and made other improvements in 2020, following government recommendations.

He acknowledged the factory started operating before receiving permits, but said it had permission to do so and that the company now has “all the environmental clearances.”

Goswami rejected the audit’s finding of “toxic dust” and said photos and videos taken outside the plant show smoke from aluminum recycling, not lead. Furnaces have protections to “effectively collect, neutralize, and filter emissions before their release,” he said.

Goswami, born in Meerut, India, said he has lived in Africa for 28 years and his businesses have created about 500 jobs. “I have never sought to take advantage of weaker regulations and enforcements,” Goswami said. He said the company has asked the Congolese government to help it find a new location for the plant in Vindoulou.

Arlette Soudan-Nonault, the Republic of Congo’s environment minister, spoke to The Examination in August, promising answers to questions about the plant's operations. “I will do the best I can,” she later wrote via WhatsApp. But she ultimately did not respond to the questions or to subsequent phone calls or messages.

The Republic of Congo’s health minister did not respond to requests for interviews. Paul Adam Dibouilou, a senior official appointed by country’s autocratic president to oversee the region that includes Vindoulou, said he cared deeply about the health of his fellow citizens but was “dubious” about allegations of high lead levels among residents.

India’s ambassador to the Republic of Congo, Madan-Lal Raigar, declined to answer questions or comment about what, if anything, India is doing to help protect the health of Congolese citizens from Indian-owned companies.

'Victory to India'

The lead recycling plant in Cameroon is separated from neighboring Congo by hundreds of miles of rainforest. It sits inside an industrial zone in the country’s largest city, Douala — a zone that Cameroon’s authoritarian government created by evicting hundreds of families, carving out more than 100 hectares in the center of town.

It was here at the start of the century that Goswami founded Metafrique Cameroun, one of the country’s largest traders of lead and other metals. In 2013, photos shared by the company on social media show men in dress shirts and South Asian kurtas at the plant watching a manager hoist the flags of Cameroon and India. One man saluted. Others stood to attention. “Victory to India,” Facebook users wrote.

That same year, a group of environmental journalists published a report that accused the battery recycling company, Metafrique Cameroun, of sickening employees and residents near the plant. None of the chimneys had filters, essential to reducing public exposure to toxic byproducts from melting lead, according to the report. Locals complained of coughs, nausea, and rashes, the journalists wrote.

“The activities of your company operate in violation of the laws of the republic and constitute a real threat to the lives of the people,” then-member of the national assembly, Isaac Ngahane, wrote to Metafrique after the news report.

In 2018, a team of university academics and scientists published the largest-ever study in Africa on the contamination of soil by lead battery recycling companies. Soil, experts say, is a major problem because lead can be swallowed by children playing outside or inhaled in dust tracked into the home on clothes or shoes.

Of the 15 companies in Africa from which soil was tested inside and outside plant premises, 8 were owned or operated by Indians and Indian firms, The Examination found. (Of those remaining, most were locally owned, records show.)

Soil tested outside the battery recycling plant owed by Metafrique returned the highest result within Cameroon and the third-highest in Africa, the study showed. That result — 19,000 milligrams of lead per kilogram — is almost 50 times higher than what the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, considers a baseline for removing contaminated soil from residential neighborhoods.

A year later, officials inspected the plant, rating it zero out of 100 for efforts to control air pollution and to address health complaints by neighbors, according to a draft report obtained by The Examination. Protecting the health of residents was the only area in which Metafrique had made no progress since operations began, according to the draft report.

Goswami said the factory had installed equipment “to ensure no gaseous or particulate matter is emitted” and he did not recall the earlier news report or communications with Ngahane, the Cameroonian politician.

“We have always been compliant with local standard regulations and legal requirements of the country we are operating in,” Goswami said.

Goswami said he and his family sold their interests in Metafrique Cameroun years ago and no longer have any interest in the company. He declined to identify the buyer, citing a nondisclosure agreement.

Cameroonian records indicate Goswami finalized in 2019 the transfer of his interests in Metafrique Cameroun to a company in the United Arab Emirates, a tax haven where the identity of owners is not made public.

This summer, a reporter for The Examination jumped into a truck with a Cameroonian geochemist, following a hazardous waste expert from the environment ministry through busy traffic to the Metafrique Cameroun plant.

“Usually when we come, we are not coming in peace,” said William Lemnyuy, the ministry official.

Over the next hour, Lemnyuy, who has represented Cameroon at United Nations’ conferences on the regulation of toxic products, wandered through the plant as workers in boots and red gloves hacked away with machetes at piles of used batteries.

Pointing to the chimney, Lemnyuy said he saw no evidence of a filter between it and the furnace. Experts consider a simple fabric filter as the bare minimum to help remove the most dangerous emissions.

“It looks like things are being done like they were 100 years ago,” Lemnyuy said.

Nearby, Kuepouo, the geochemist and executive director of the nonprofit Research and Education Center for Development, scraped topsoil into bags, sending them to an overseas laboratory for lead analysis.

The Examination paid scientists to collect and analyze soil samples from inside the plant and up to 275 meters away.

Kuepouo started work bent over a strip of earth where rocks, a fabric sack, and an old BMW part lay in trash piles. He and a colleague then fanned out west, past lunch kiosks and crowded homes to the local high school, a complex of concrete buildings where mold streaks the walls. As a final stop, the scientists headed northeast from the plant, down a muddy path, to collect soil near a health clinic run by a Bolivian nun.

“We can definitely say soil contamination is coming from the plant,” Kuepouo said after reviewing the results. Soil from inside the factory showed lead at more than 70 times the level at which the U.S. EPA recommends cleaning up an industrial site. Other samples, including those taken near women grilling and selling corn near the factory, were six to eight times higher than what the U.S. agency considers a threat to public health. Lead in soil near the health clinic and school did not rise to levels of concern, according to the analysis.

Testing soil helps establish a pattern: If lead levels decrease farther from a plant, the more likely it is the plant is the source, scientists say.

Kuepouo said the results showed higher levels of lead than previous testing. “Things are getting worse,” he said.

Lemnyuy said some companies in the industrial zone where Metafrique Cameroun operates have improved their efforts to stop lead and other particles from raining down on surrounding communities, installing systems to cover and capture smoke and gas. Metafrique Cameroun, he said, has not.

The current approach of Cameroonian regulators is to work with industry, not penalize it, he said.

“It’s like beating a child because he or she is wetting the bed,” Lemnyuy said. “If you just keep on beating the child, the child might not feel like you are really helping. … It’s the same thing with the industry.”

Ahmed Jaber, director general of Metafrique Cameroun, said the company uses high-quality filters that are replaced every six months as well as other equipment to control pollution. Responding to questions about Lemnyuy’s July inspection, Jaber said, “Filters were under maintenance as some bags would have been worn out or destroyed by too much heat during the time of the visit.”

Jaber also denied the findings of the 2019 inspection and said reports made no reference to health hazards. He did not share reports.

The same day, Kuepouo and Lemnyuy visited the two other battery recycling facilities in Douala — both Indian-operated. Tests from soil inside and outside these facilities also showed elevated lead levels.

The ministers of health and environment in Cameroon did not respond to phone calls and letters seeking an interview. Albert Mambo, a Health Ministry official responsible for Douala, told The Examination he had no information about battery recycling plants.

“Our concern is more like tropical diseases or emerging illnesses,” he said. “There has to be an order of priority,” Mambo said of lead.

Earlier this year, Metafrique Cameroun exported lead to Spain, Ireland, and other countries. Containers of lead from Metssa Congo, owned by Goswami, arrived last month via cargo ship in the Port of Baltimore. The recipient was Trafigura Trading LLC, the U.S. subsidiary of the global trading giant Trafigura, trade records show.

The records do not indicate where the lead went after arriving in the United States, and Trafigura declined to comment on its destination.

Responding to questions about community complaints against Metssa Congo, a Trafigura spokesperson said, “We take these allegations very seriously and are investigating this further.”

'Local Chernobyl'

Other Indian-operated battery recycling companies in Africa have drawn criticism from officials, scientists, and community members.

Of those, none is more conspicuous than Gravita India Ltd.

“Our operation is mostly in Africa,” an executive told shareholders earlier this year. A major Indian research firm has called Africa the company’s “crown jewel,” pointing to growing profits and favorable government policies. Gravita recently reported global revenue worth more than $336 million.

In 2011, officials in Senegal faulted the company for failing to adopt dozens of safety recommendations, according to media reports. The plant, located in a town that is home to an orphanage and a children’s hospital, was a “local ‘Chernobyl,’” one resident wrote. The company denied responsibility for any sickness or pollution, media reported. The plant has since been moved.

In 2013, government scientists in Ghana and academics found lead levels within the Gravita factory to be thousands of times higher than the average level within U.S. industrial sites. A second study years later also found unsafe levels of lead in soil on company premises.

“They came in at a time when everyone thought that recycling was good and should not be regulated,” Kwame Aboh, the former deputy director general of the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission, said of Gravita. Aboh participated in the 2013 study with other scientists at the commission, which runs a soil research center. He worried about workers he saw using sledge hammers to break batteries. “I think we were all a bit lax,” Aboh said.

Pwamang, Ghana’s former environmental chief, told The Examination the agency ordered Gravita to decontaminate the site and relocate. “But they didn’t do a cleanup as such,” Pwamang said. “That site is still highly contaminated.”

Gravita did not respond to emails seeking comment or a letter delivered to its Ghana office.

Back in Senegal, near the farming village of Ndiakhatt, sits a battery recycling company named after Ganesha, the elephant-headed Hindu god.

Residents who live near the plant fear sickness and death, a repeat of the worldwide scandal years ago when 18 Senegalese children died from brain injuries thought to be caused by long-term exposure to lead from an unauthorized recycling operation.

Last year, the environment ministry in Senegal ordered the suspension of Ganesha’s plant after an inspection showed the company started work without necessary environmental protections, according to a letter obtained by The Examination. Officials also found elevated lead levels in soil during the inspection, the letter stated, adding “the alarming pollution situation observed on the site requires urgent measures to stop activities.” Authorities have since allowed operations to resume.

“We will not wait for the death of our children to react,” locals protested in May, marching to demand the permanent closure of the plant.

An employee of Ganesha Senegal denied wrongdoing, saying the closure was due to a misunderstanding. He said Ganesha’s competitors were behind the complaints, but declined to identify the companies responsible.

“We are not polluting the environment,” said the employee, who declined to give his name. “If we are doing any violation of the environmental law, then how are we allowed to start again?”

The environment minister of Senegal did not respond to phone calls and messages seeking interviews.

Dead-end in India

Indian Prime Minister Modi has made doing business in Africa and close relationships with its people a cornerstone of his foreign policy.

In September, Modi hugged the president of the African Union, the regional bloc representing every country on the continent, announcing the union had gained membership in the G20, a forum of the world’s most influential economies.

“When we say we see the world as a family, we truly mean it,” Modi said earlier this year.

Yet people in Africa say they don’t feel like family and instead face formidable barriers to seeking recourse from New Delhi.

India — unlike the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and other major corporate hubs — has no specific legal tool for victims of corporate misbehavior overseas. Even China, which has long faced accusations that its homegrown firms have harmed human health, earlier this year authorized foreigners to seek justice from certain Chinese companies operating overseas.

In 2016, residents of Mombasa, an ancient trading city in Kenya sued an Indian-owned battery recycling plant that had long stood accused of causing locals to collapse from kidney failure, writhe from diarrhea, and lose their memory. At least 20 people had died and stillborn fetuses looked sooty, locals said.

Neighbors in Mombasa filed the lawsuit against Metal Refinery EPZ Ltd. as well as government agencies that allowed the battery plant to operate.

The company did not respond to the lawsuit, records show.

“We attempted to trace them in India … but it was impossible,” said Phyllis Omido, a community leader who faced down anonymous threats and government pressure to end the legal campaign. “We had no help from the Indian consulate here, and the Indian authorities were not helpful.

Indian authorities did not respond to emails, faxes, or phone calls seeking comment. The plant in Mombasa has since closed.

In 2020, a judge in Kenya awarded residents $12 million. In June, an appeals court overturned the ruling and ordered a retrial.

India wasn’t always so quiet in the face of corporate abuses by foreign-owned businesses.

One midnight in December 1984, plumes of poisonous gas escaped from a factory in Bhopal, India, that was owned by a Connecticut-based chemical manufacturer.

Thousands were killed by methyl isocyanate, which drowned some in their own bodily fluids and caused the hearts of others to stop. At least 15,000 people died and half a million were blinded, disabled, or sickened in what is one of the worst industrial accidents in history.

Indian officials filed criminal charges against the local company and its managers as well as the U.S. parent company and its chief executive Warren Anderson.

To reach Anderson, the Indian government published a notice in the Washington Post, summoning him to appear in court. Anderson refused, and the case dragged on.

“The tragedy was caused by the synergy of the very worst of American and Indian cultures,” Bhopal Chief Judicial Magistrate Prakash Mohan Tiwari wrote years later. “An American corporation cynically used a third-world country to escape from the increasingly strict safety standards imposed at home.”

The U.S. government declined to extradite Anderson, who died in 2014.

The response to the catastrophe in Bhopal paved the way for other lawsuits by victims of corporate harms that continue today. In one unsuccessful case, victims of a government massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo attempted to sue a mining company in Australia and Canada for allegedly providing trucks and provisions to soldiers.

Thousands of Nigerians living near oil pipelines are seeking compensation in an ongoing case from the London headquarters of Shell, arguing the company controlled a subsidiary that poisoned land and groundwater.

Residents of the Zambian city of Kabwe are suing a South African mining company for alleged lead poisoning. Plaintiffs allege the company knew of health risks while operating a lead mine in Kabwe, which researchers have called “the world’s most toxic town.” The case is ongoing.

Victories are rare and hard-fought. But experts say formal avenues for complaints, in courtrooms or beyond, can be worthwhile. Fifty-one countries, from the United States to Morocco, have so-called “national contact points,” government-backed bodies with the power to investigate complaints of corporate wrongdoing abroad. Contact points have no enforcement powers but can make recommendations and help in negotiations between a company and individuals or communities.

“As the overseas footprints expand and human rights abuses linked to Indian companies get exposed, I expect the Indian government to come under increasing pressure to proactively regulate conduct of such companies,” said Surya Deva, law professor at Macquarie University in Australia and a former member of the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights.

For now, the residents of Vindoulou are pressing their case in local court. More than 150 people joined a lawsuit in June, asking a judge to recognize the dangers they face, shut down the company, and force it to relocate. The judge dismissed that case in September, holding the civil court had no power to rule on administrative matters.

Last month, Ndembi and neighbors filed a fresh lawsuit before an administrative court, seeking — once again — an order that Metssa Congo stop operations and compensate those with elevated lead levels in their blood. “There is an emergency and time is of the essence,” an attorney for the residents wrote.

At home, Ndembi and his family still cough during the day and wake at night from the noise. With limited Internet connection, Ndembi figures the best thing he can do is stand in his garden with his phone, filming the factory as its chimneys darken the sky.

One day, he hopes, the videos will make a difference.

This story was produced by: